“The engine takes your models and adds collision, gravity and such so characters won’t fall through floors or walk through walls.” It also brings the surroundings to life. For that, de Boer enlists a powerful software called Unreal Engine, which essentially adds physics to the world he’s created. The thing is, the game still isn’t playable at this stage. Once he finishes making all the objects in HD, he loads everything into the recreated level and adds the necessary texture - “grass, shading, bricks and all sorts of stuff to bring more life into the scene.” To do this for every level, de Boer extracts the original files from the game and uses them as a template, especially for sizing and dimensions within the world. For example, Wet Dry World is a level where the water rises as the player hits these objects, but the water never actually came from anywhere, so I gave the level pipes that spew out water and then drain again.” De Boer’s computer at work “Occasionally, the low-resolution of the original art is so poor - or things are missing - that it’s hard to tell what the artists were going for. “But not too many details,” he adds, “because it still needs to maintain the feel of the old game.”įrom time to time, too, he just has to use his imagination. The same goes for every tree, cannon, bush, brick wall and, well, everything else. He needs to add realistic hair, stitches on all that denim and more to give him the depth of detail contemporary gamers expect. And because expectations around graphics and detail are so high today compared to 1996, he can’t just throw blue overalls on Mario and call it a day.

Because the only thing he’s really “recreating” is the gameplay.

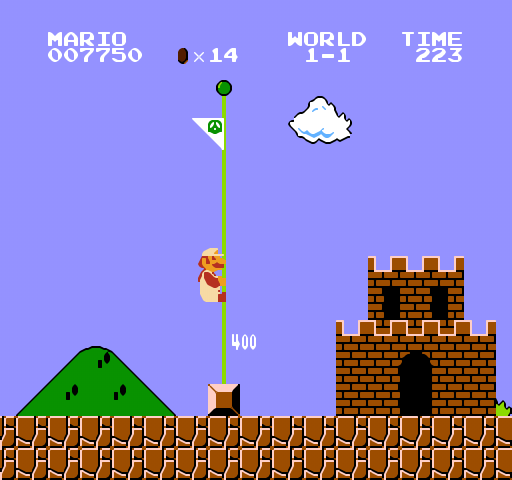

To that end, “recreating” is probably the wrong word. You can’t just take a 3-D model from the original game and put it in your remake, because it would look terrible,” he explains. “You have to redo everything: 3-D models, textures, music, sound effects, characters, animations, everything. In fact, recreating the game has become a game itself, de Boer says, so much so that he loses track of time when he’s working on it. And if you love the game as much as I do, it’s worth it.” “But I’m passionate about it because I’ve loved the game since my childhood. “It’s a painstaking process,” he says of restoring the 1996 game, which was Nintendo 64’s flagship title and is still considered one of the greatest games of all time. Nearly six hours a day for the last three years, 24-year-old Harold de Boer has been mapping, measuring and remastering every single pixel in Super Mario 64 - even down to each blade of grass.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)